Let F be a Field

The first time I remember seeing the sentence “Let be a field” I had the same feeling you get when you walk into an American kitchen and there’s already a tray of ice cubes sitting there like a small, polite miracle.

Not because ice cubes are deep. Because they’re assumed. They’re infrastructure. They’re the silent background music of expectation: water is cold, toilets flush, there is paper, there is soap, there is a mechanism by which your body’s humiliations can be processed and forgotten.

Then you come back to Calcutta and the universe hands you a different set of axioms.

Sometimes the restroom is a philosophical prank. Sometimes it’s a war crime against the concept of dignity. Sometimes it’s a tiled cubicle with the emotional aura of a medieval oubliette where you realize—very quickly—that “expected amenities” are not a human right, they’re a local theorem, and here your theorem does not hold. There is no paper. There is no water. There is, occasionally, a broken tap that produces one resentful dribble like it’s being paid per molecule.

And you stand there with your civilized assumptions—your little ice cubes of certainty—melting in real time, and you understand what mathematicians mean when they say “assume the following.”

A field is that kind of assumption. It’s a tiny constitution for arithmetic. A well-equipped framework of overcomplicated jargon that, when you strip it naked, says: you can add, you can subtract, you can multiply, and if you have a nonzero thing you can divide by it without the universe throwing a chair. The end. That’s the whole scandal.

But mathematicians, being the sort of people who can’t order tea without defining a sigma-algebra, decided to write it as a list of “axioms,” which are really just a way of demanding that your arithmetic doesn’t turn into a street brawl.

- Closure — no surprise outsiders sneaking in.

- Associativity — so you don’t have to parenthesize like a madman.

- Commutativity — so doesn’t behave like a Bengali queue where position is an opinion.

- Identities — and , the two most important freeloaders in human history.

- Inverses — so every number has a way to undo itself, and every nonzero number has a multiplicative escape hatch.

- Distributivity — so multiplication plays nicely with addition instead of sulking in a corner.

If you hand me any set where all that is true, I will call it a field and go on with my life. If you don’t hand me that, then linear algebra starts behaving like Calcutta plumbing: things still flow sometimes, but only if you develop a suspicious intimacy with blockages.

Why the name “field” is so weird, and why Germans were involved

It is a delicious linguistic oddity that mathematicians chose the word “field,” which in normal English means a place where cows stand and contemplate their inevitable conversion into curry, to mean “a place where division works.”

The Germans were there first, of course. They used Körper—“body,” “corpus”—for the idea of a number system closed under the four operations, a phrase that always makes me think of an organism: self-contained, internally coherent, not leaking algebra onto the carpet. Dedekind is commonly credited with using Körper this way around 1871.

Now, Germans naming something “body” makes perfect sense. Germans can name anything. They can name a feeling you didn’t know you had while staring at a closed bakery on a rainy Tuesday. So Körper is tidy: arithmetic is a body, a whole creature.

English, however, has the attention span of a squirrel in traffic, and we did not keep “body.” We went with “field,” which sounds pastoral and harmless and completely fails to warn you that you’re about to spend the next decade proving theorems about polynomials that behave like cursed jewelry.

The English term field in the modern algebraic sense is usually attributed to Eliakim Hastings Moore, an American mathematician, who used phrases like “field of order ” and “Galois field” in the 1890s—famously around the Chicago math congress era (1893).

So yes: Germans gestated the concept in their orderly, cathedral-like prose; then English-speaking mathematicians—particularly Americans—gave it a name that sounds like a place you’d take a picnic. That’s civilization for you: you invent something profound and then label it like a children’s book.

Moore, Weber, Steinitz: the bureaucrats arrive

Moore didn’t invent fields out of pure ether. The century was already thick with the smell of algebraic smoke—polynomial equations, Galois theory, number fields, function fields. People were using these structures before they were fully christened and standardized, in the same way Calcutta uses “traffic patterns” without ever agreeing on the existence of lanes.

Around the same time, Heinrich Martin Weber gave one of the first clear abstract definitions of a field (late 19th century; often cited as 1893), and then Ernst Steinitz, in 1910, did what the Germans do best: he systematized the whole thing into a grand theory—Algebraische Theorie der Körper—the paper that makes “field theory” feel like an actual subject rather than a set of clever ad hoc tricks.

This is the part of mathematical history that always makes me want to laugh and sigh at the same time: first we have wild invention—ideas sloshing around, half-defined, used because they work—and then the bureaucrats of rigor show up with clipboards and stamps and say, right, we’ll need a definition, and a classification, and a set of standard lemmas, and we’ll call the whole enterprise “field theory,” which sounds like a career in irrigation.

And it matters. Because once you define a field cleanly, you can stop re-proving the same little hygiene facts every time you do algebra. You no longer have to check, nervously, whether division is going to betray you. You know your nonzero pivot has an inverse. You know subtraction won’t kick you in the teeth. You can build.

A field is just “arithmetic with amenities”

I keep coming back to the restroom metaphor because it’s vulgar and therefore honest.

A field is arithmetic with amenities. It’s the math version of “there will be toilet paper and it will not be counterfeit tissue that disintegrates into confetti the instant it meets reality.”

You can do arithmetic in lots of places that are not fields. The integers are a perfectly respectable neighborhood: you can add, subtract, multiply, no problem. But division is a scandal. Try to divide 1 by 2 and the integers look at you like you’ve suggested sacrificing a goat on the living-room carpet. You can say , but it doesn’t live there. It’s an immigrant. It needs a different citizenship.

That’s why we have this ladder of “number systems” you meet as a child, each one created by someone who got tired of being told “you can’t do that here.”

- Natural numbers: subtraction breaks.

- Integers: division breaks.

- Rationals: you can divide, but not solve cleanly.

- Reals: you can solve that, but then polynomials demand complex numbers like a spoiled prince demanding a third dessert.

- Complex numbers: now you can solve every polynomial, but you’ve lost ordering; you can’t say which number is bigger without starting a philosophical bar fight.

A field is the moment where you say: for my purposes, I want the amenities of rational arithmetic—division by nonzero things—and I am willing to encode that as law.

The America I lived in, and the America now

When I first came to the United States (late 90s, the era of dial-up shrieks and optimistic tech brochures), the country had the same vibe as a good algebraic structure: a slightly smug assumption that the basic operations work.

You wanted to open a bank account? It worked. You wanted to buy a sandwich? It worked. You wanted to argue with a professor about whether your proof was valid? It worked (and you could do it without anyone asking which god you prayed to first).

You wanted to find a restroom in a gas station off the highway? There was paper. There was soap. There was an unspoken pact between strangers that bodily maintenance would remain private and mostly dignified.

It wasn’t utopia. It was empire with good plumbing. But the plumbing mattered, because it created a psychological baseline: a sense that the “axioms” of daily life were stable enough that you could waste your brain on abstract problems like whether a certain set is closed under multiplication.

Now, in the Trump era—this carnival of grievance and performance and permanent campaigning—the country often looks like it’s experimenting with life over a ring instead of a field. Division fails. Inverses don’t exist. Every disagreement becomes “you’re either with us or you’re a traitor,” which is a very efficient way to destroy a shared algebra.

I say this with caution because memory is treacherous and nostalgia is a liar with good handwriting. But the contrast feels real: the older America I experienced was confident in its infrastructure, while the current one seems delighted to set fire to its own axioms and then argue about whether fire is woke.

Of course India has its own bonfire of axioms—ours is older, smokier, more mythologically decorated, and we’ve been roasting ourselves on it for centuries with great spiritual enthusiasm and poor sanitation—so I’m not delivering a supremacy sermon here. I’m just saying: societies, like algebraic systems, depend on boring rules holding quietly in the background. When those rules become negotiable, everything becomes expensive.

Why linear algebra cares so much about fields

Linear algebra is, at heart, the study of solving many equations at once without losing your mind.

You have vectors. You have matrices. You have systems like . You have the intoxicating promise that you can reduce messy reality to a grid of numbers and then do things to it—rotate it, project it, solve it, diagonalize it, compress it, make it confess.

But none of that works smoothly unless your scalars—the ordinary numbers you multiply vectors by—live in a field.

Because Gaussian elimination, that humble algorithmic workhorse, repeatedly does one scandalous act: it divides by the pivot. Over a field, that’s legal as long as the pivot isn’t zero. Over something that’s not a field, you can get stuck. You can have nonzero elements that don’t have inverses. You can have solutions that exist but can’t be reached by the usual clean steps. The whole business turns from “linear algebra” into “linear algebra, but with tragic complications and supplementary paperwork.”

This is why a vector space is defined over a field. The field is the reliable currency. The vectors are the objects you’re buying and selling. If your currency can’t make change—if division fails—then your nice geometric intuitions start falling apart.

And then you meet the next concept, like a new level in a video game: if you replace the field with a ring, your “vector spaces” become modules, and modules are wonderful and deep and also, sometimes, a haunted house. The same equation may have many solutions or none, because you can’t just divide by .

So, fields are the quiet enablers. The background assumption that lets linear algebra be the crisp, geometric, almost cinematic subject that makes people fall in love with mathematics: planes slicing through space, shadows on walls, eigenvectors standing stubbornly in place while the world stretches around them.

Without fields, that cinematic clarity turns into a Bengali government office: still theoretically functional, but everything takes longer and you need a stamp.

The joke, and the not-joke

The joke is that a field is “just” a set with operations that behave like rational numbers. The not-joke is that this “just” is the difference between a world where you can build a cathedral of theory and a world where every step requires improvisation.

This is why the history matters. Because the concept of a field didn’t arrive because mathematicians love abstraction for its own sake (though some do, and I salute their weird little hearts). It arrived because the algebra demanded a clean stage.

- Solving polynomial equations forced people to enlarge number systems.

- Number theory forced people to understand extensions—what happens when you adjoin roots that don’t exist yet.

- Geometry, especially the algebraic kind, forced people to treat functions and coordinates as living in their own number universes.

And at some point, someone said: we keep encountering these number-like systems where arithmetic works reliably; we should give that reliability a name, bottle it, label it, and stop reinventing it.

So: field.

A word that makes it sound like wheat, but actually means: the rules won’t betray you. Not today.

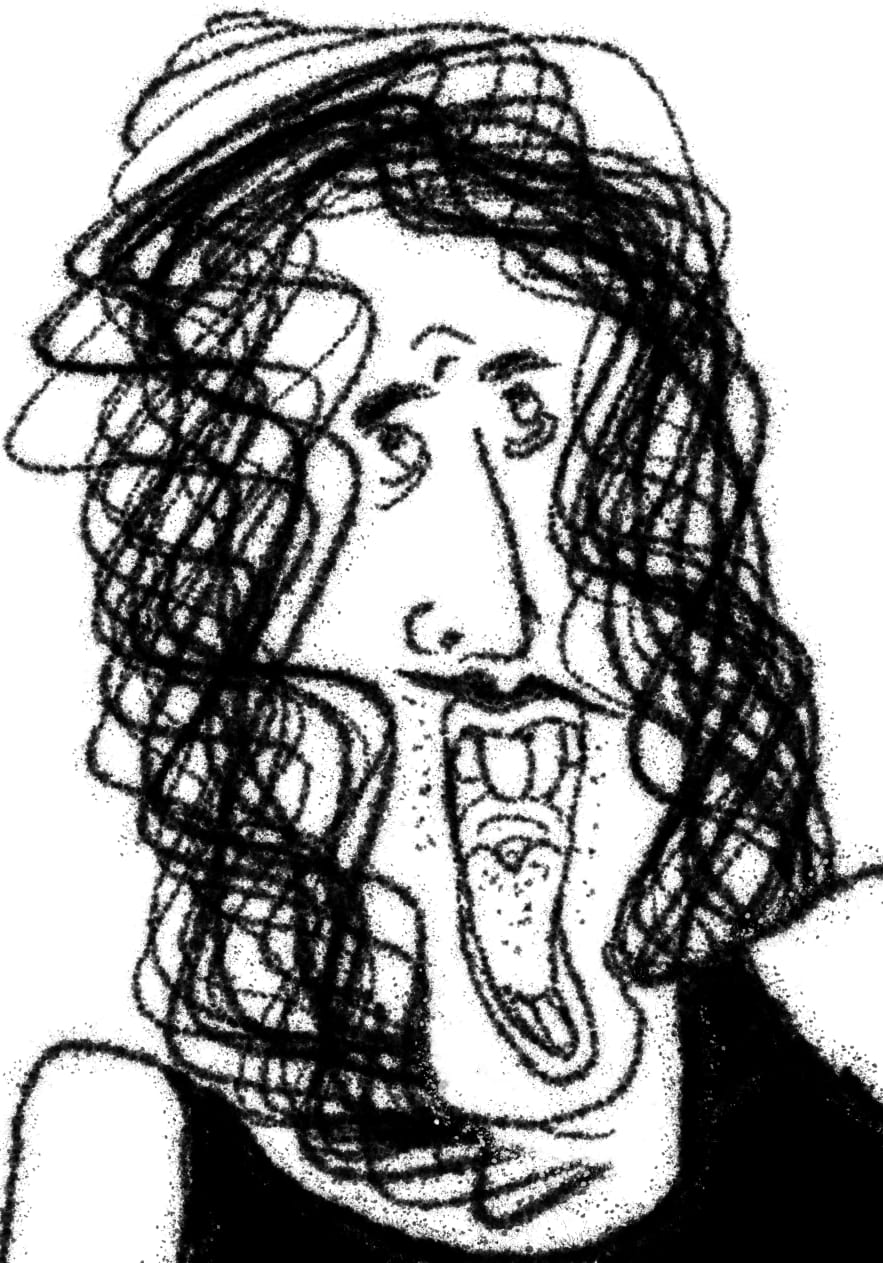

Small personal confession, because my moods are part of the apparatus

When I’m hypomanic, the word “field” feels like freedom. Like, yes, give me axioms, give me structure, give me a clean little universe where the inverse exists and the distributive law holds and I can finally stop negotiating with chaos.

When I’m depressed, “field” feels like another smug certificate issued by the empire of abstraction, another club with velvet ropes, another reminder that my real life does not have inverses—some mistakes don’t undo, some debts don’t cancel, some losses don’t factor nicely.

And then, because I’m me, I oscillate. I want the cleanliness of a field and I also want to throw the whole apparatus into the Hooghly and watch it float past the idols and the sewage and the prayers.

But I keep coming back. Because a field, for all its jargon, is a kind of promise: if you can agree on a few simple rules, you can build something that doesn’t depend on who’s shouting loudest.

Tonight I open my notebook—cheap paper, slightly rough, the kind that absorbs ink like it’s thirsty—and I write, almost as a ritual, almost as a superstition:

Let be a field.

Then I pause, as I always do, and I think of ice cubes, and of the strange luxury of assumptions, and of how much of civilization—mathematical or otherwise—is just a collective decision to keep the basic operations working.

I close the notebook, not triumphantly, just quietly, like turning off a light in a room that has been arguing with you all day.