Ruminative Piss

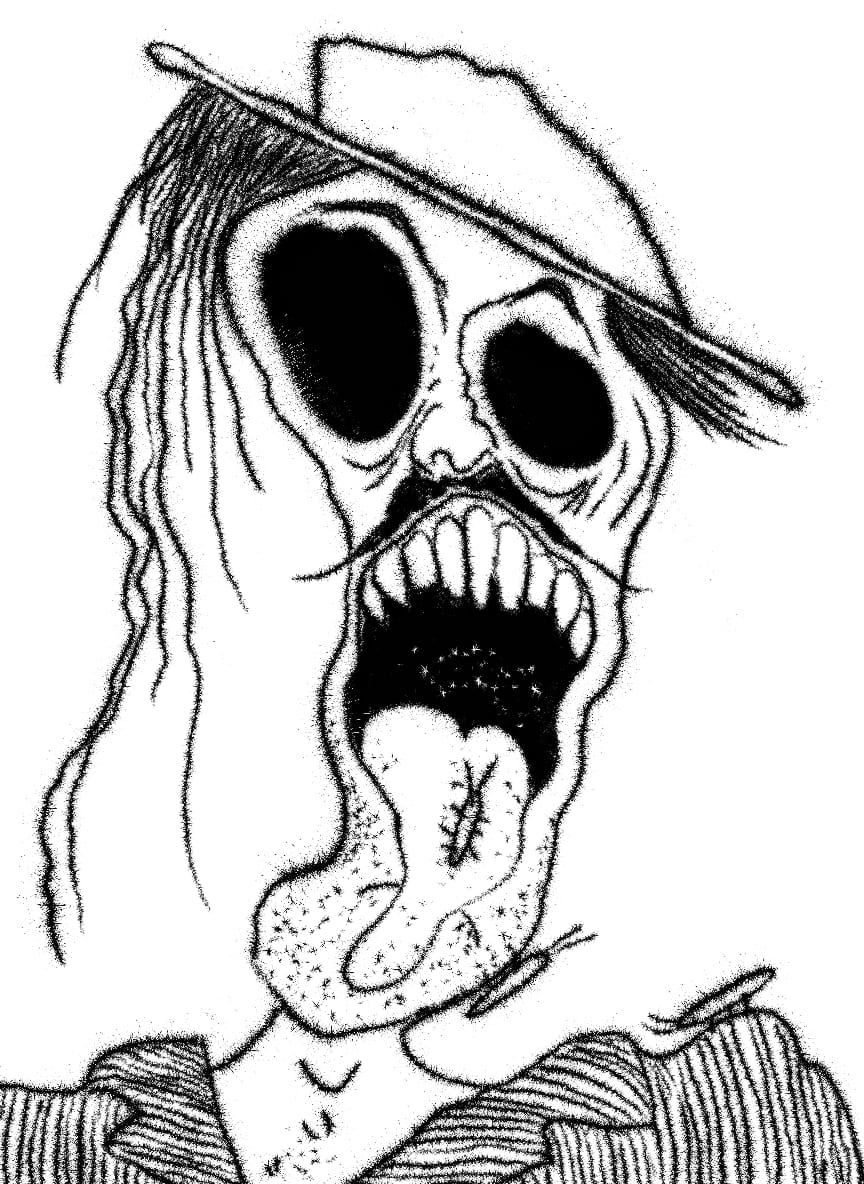

I have the picture open on my phone like a talisman I don’t trust, a little black-and-white man with a belly like a punctuation mark and a grin like a lie, tilting his head back to swallow something that is colored an indecent, almost cheerful yellow, the kind of yellow that belongs on a child’s plastic toy or the warning sticker on a pesticide bottle, not in the mouth of a grown man who already knows what his mind does when it wants to be cruel. You can see the metaphor I hope.

The room is doing its usual North Calcutta winter performance: air that looks innocent and smells like a committee decision, ceiling fan chopping lazily at nothing, a glass of water that tastes faintly of metal because everything tastes faintly of metal when you live in a city built from exhaust and resignation.

On the table sits a blister pack of pills—each tablet sealed like a tiny hostage negotiation, each one a choice between two embarrassing faiths: the faith that chemistry can patch a brain, and the faith that my brain is even patchable.

I pick one out. The foil gives that little crackle like it’s snickering. The yellow tablet sits on my fingertip, absurdly small for something that can rearrange the furniture of your inner universe. I swallow it, and for a second it sticks to my tongue like a rude guest who won’t leave, and my mind—being the considerate host that it is—immediately serves it a full meal of thoughts:

You’re pathetic. You’re late. You’re wasting your life. You’re a burden. You’re a joke. This pill is a joke. Your entire biography is a joke with footnotes.

That’s the snare. Not sadness itself. Sadness is honest. Sadness says: something hurts. Sadness is a bruise you can point to.

Depressive rumination is a different species. It’s my brain brewing a rancid little drink from old disappointments, future catastrophes, and the fermented sludge of comparison—and then insisting, with the confidence of a drunk uncle at a wedding, that what it’s serving is truth.

And I, in bipolar II depression, am perfectly capable of drinking it like it’s spring water.

The Liquor of Certainty

People use the word “rumination” as if it’s a thoughtful thing, like a philosopher in a library stroking his chin, or a gentle cow in a field contemplating the metaphysics of grass.

The word is much more vulgar than that. It comes from Latin ruminare, to chew over; and behind that is the rumen, the first stomach of a ruminant—cows, goats, deer—those animals that swallow, then bring it back up, then chew it again, as if the universe might cough up a better flavor the second time.

Bos taurus does this with grass because grass is an engineering problem. Cellulose is stubborn. You need multiple passes, enzymes, microbial assistants, an entire internal factory to wring nutrition from something that is, to begin with, basically green cardboard.

Humans do it with thoughts because… because we can.

That’s the humiliating part. The cow has a reason. I do it because my nervous system is a gossip columnist with a chemistry set. In depression, the cud is always the same: a sentence I said wrong, a friendship I didn’t maintain, a door I didn’t knock on hard enough, a phone call I didn’t make, a version of myself that existed in some alternate timeline where I was less frightened and more disciplined and didn’t turn every ambition into a half-finished notebook.

The mental process feels productive because it has the shape of thinking—there’s motion, there’s repetition, there’s the little click-clack of logic pretending to be a train heading somewhere. But what it is, most of the time, is my brain chewing the same dead leaf until it’s convinced it has found the leaf’s hidden moral message: You are the problem.

And here’s the trick that makes it a snare rather than a habit: the conclusions arrive with the flavor of fact. Not “I feel like a failure.” Too honest, too provisional. No—depression prefers the courtroom voice. “You are a failure.” Full stop. Case closed. Court adjourned. Everyone go home.

I have been inside that court. I have been the judge, the prosecutor, the incompetent defense attorney who falls asleep during cross-examination, the stenographer typing “pathetic” for the fiftieth time, and the accused sitting there thinking, Yes, yes, that’s fair.

How My Mood Becomes a Measurement Device

Somewhere in the back of my bookish skull there’s a little mathematician who wants to model everything, because models are clean and life is a public toilet. So I try to imagine what depression is doing in technical terms, not to “solve” it (nothing makes an illness laugh harder than being treated like a puzzle), but to keep my dignity by describing it accurately.

Here’s one version. The brain is a prediction machine. It’s constantly making guesses about the world—what will happen next, what people mean, what a sensation implies—and updating those guesses based on incoming data. If you want a nerdy picture, think of a kind of Bayesian update: prior beliefs plus evidence yields a posterior belief. You start with some expectation, you see something, you adjust.

In a well-behaved system, the confidence you assign to evidence matters. Noisy data gets downweighted. Reliable signals get honored. You don’t let one bad measurement convince you the planet has changed shape.

Depression, at least the depression I know, behaves like a sensor that has lost calibration and refuses to admit it. It doesn’t just deliver “negative thoughts.” It delivers them with high precision—as if the measurement error has dropped to zero. As if the instrument is perfectly trustworthy.

The thought arrives: No one cares about you. And the brain stamps it with the seal: CERTIFIED TRUE. The thought arrives: You will never fix this. Stamp: TRUE. The thought arrives: Your best years are behind you. Stamp: TRUE, with a flourish, as if the stamp itself is enjoying the performance.

Meanwhile, the actual evidence—people being kind, small accomplishments, the mere fact that moods change—gets treated as noise. Anomalies. Statistical outliers. “Doesn’t count.”

So I end up with a grotesque inversion of scientific method: my worst state becomes my most “accurate” state. Which is idiotic. It’s like insisting that a microscope is most reliable when someone has smeared Vaseline on the lens.

Piss, Alchemy, and the Seduction of Extracting Meaning

The phrase I used—drinking ruminative piss—sounds like the kind of line that should get me banned from polite dinner parties, which is fine because I don’t go to polite dinner parties. But it’s also weirdly scientific.

Human beings have a long, proud history of doing disgusting things in the name of discovery. We have boiled corpses, dissected cadavers in candlelight, scraped mold off bread to make antibiotics, and—here’s my favorite—made light out of urine.

In the 1600s, a German alchemist named Hennig Brand tried to isolate the Philosopher’s Stone, because of course he did, and he decided urine was the right starting material, because urine contains “essence” and other words that mean “I have no idea what I’m doing but I’m committed.”

He collected buckets of it—imagine the smell, imagine the neighbors—and boiled it down, fermented it, heated it, distilled it, until he got a waxy substance that glowed in the dark. Phosphorus. From piss. Literal light from waste.

If that doesn’t summarize Homo sapiens, I don’t know what does: we are capable of turning the most humiliating bodily byproduct into something that can set ships on fire and also help plants grow.

So the problem isn’t that the mind generates waste. The mind generates waste the way the body does: constantly, inevitably, with a kind of bored competence. The problem is what I do with it.

Brand didn’t drink the urine. He processed it. He subjected it to heat and transformation. He treated it as raw material, not as a beverage. Depressive rumination is me doing the opposite: taking the raw effluent of a sick mood and swallowing it, unfiltered, and then acting surprised when it poisons my perception.

The snare is not merely pessimism. The snare is credulity. I become an alchemist who confuses his starting sludge for his final product.

The Two Americas in My Head

When I was in America—those years between 1998 and 2014—there was an ambient faith in systems that I didn’t fully share but could at least recognize as a real cultural weather pattern.

The airport lines moved with a kind of stern efficiency. The forms were annoying, but they were legible. The shelves were stocked. The roads had rules that mostly worked. Even the nonsense had a disciplined, bureaucratic geometry to it, like a well-designed machine that occasionally pinches your finger.

I’m not romanticizing it. I saw poverty. I saw loneliness. I saw the quiet brutality of “meritocracy,” that lovely word people use when they want to believe their luck is virtue. But there was still a baseline belief that if you measured something, if you recorded it, if you argued about it, reality would eventually submit to some shared accounting.

Now, observing America from afar—the news clips, the algorithmic tantrums, the way every topic becomes a blood sport—I see something else: a nation caught in its own version of rumination, chewing the same fear until it tastes like prophecy.

The mechanism is identical to my depressive snare. A mood becomes a worldview. A feeling becomes a “fact.” A narrative becomes immune to counterexample. Everyone is certain. Everyone is furious. Everyone has a stamp.

And the funniest, saddest part is that this is happening in a country that gave the world so much of its modern infrastructure for truth-making: peer review, statistical literacy (in pockets), scientific institutions, investigative journalism, the whole Enlightenment apparatus with its powdered wigs and its beautiful, doomed optimism.

Indian Education and the Cult of the Wrong Certainties

India, meanwhile, has its own specialty: teaching certainty without teaching the method by which certainty is earned. We cram. We memorize. We recite. We learn to perform answers the way a parrot performs devotion.

We are trained, from childhood, to treat authority as epistemology. If it’s in the book, it’s true. If it’s said by a teacher, it’s true. If it’s said by a loud man on a stage, it’s true. If it’s said with enough conviction and a microphone that squeals, it becomes truer. And then we grow up and wonder why fraud flourishes like algae.

My depression loves that cultural training. It uses the same template. A thought appears with authority—because it is loud, because it is repetitive, because it has the tone of certainty—and I accept it the way I accepted textbook definitions as a child: obediently, fearfully, as if disagreement is a moral defect.

Depression is an internal authoritarian regime. It doesn’t debate. It declares.

The irony is that I’m an atheist, a skeptic, allergic to grandstanding, the kind of person who will argue about the misuse of a word in a newspaper headline—yet the loudest tyrant in my life is a mood state, and I still hand it the keys.

The Mechanical Snare

Rumination is seductive because it has the moral aesthetic of effort. If I lie in bed doing nothing, I feel guilty. If I lie in bed thinking miserable thoughts, I feel… industrious. As if I’m paying rent for my existence by suffering.

This is the puritanical accountant in my skull: misery as proof of seriousness.

So I pace mentally, revisiting old scenes like a director reshooting the same bad movie, convinced that if I find the right angle—if I replay the moment with enough precision—I will discover the secret lever that makes the story different. But the past is not a machine with a hidden gear. The past is a dead animal. Chewing it does not resurrect it. It just gives you the taste of rot.

In bipolar II depression there’s also a special cruelty: the memory that I have been other versions of myself. I have had days when my mind is quick, when connections sparkle, when I can write with that slightly manic electricity where everything is linked—history to math, etymology to politics, the smell of winter air to the concept of entropy.

And then the depression arrives and says: That was an illusion. That was you being delusional. This—this heaviness, this contempt, this certainty of doom—is the real you.

A Brief Zoology of My Thoughts

Some thoughts are like mosquitoes. Annoying, high-pitched, easily slapped away if you’re awake enough. Some thoughts are like stray dogs: persistent, hungry, capable of following you for miles, not evil, just desperate.

Depressive ruminations are like feral pigs that have discovered the pantry. They don’t just intrude. They rearrange the house. They knock over chairs. They root around in every corner until you can’t remember what the room looked like before they arrived.

And the worst ones have costumes. They dress up as philosophy: Life is meaningless; everything decays; all effort is vanity. They dress up as economics: The system is rigged; you have no leverage; you will always lose. They dress up as morality: You are selfish; you are weak; you don’t deserve care. They dress up as “realism,” that fashionable word people use when they want to confuse cynicism with accuracy.

Sometimes they even dress up as compassion: You should withdraw so you don’t bother anyone.

That’s a particularly vile disguise, because it makes self-erasure feel like virtue. I have to remind myself—often in the most blunt, unpoetic language possible—that a thought being elaborate does not make it true. The brain can produce nonsense at any IQ level. In fact, high IQ nonsense is the most dangerous nonsense, because it comes with citations.

The Small Counterspell

There is a modest practice I return to, not as salvation, not as cure, but as a way to keep my head above the swamp. I try to treat thoughts the way I treat weather.

When it is humid and polluted outside, I do not conclude: The universe is made of poison. I conclude: The air is bad today. Then I close the window, run the fan, drink water, wait.

Similarly, when my mind is producing the bleak, contemptuous, ruminative piss of depression, I try—try, imperfectly, sometimes with theatrical failure—to say: This is a mood. This is chemistry. This is weather inside the skull.

Not “fake.” Not “invalid.” Weather is real. It just isn’t the whole climate. Depression wants me to confuse a storm for the planet.

So I do something that feels childish but is, for me, a form of scientific hygiene: I write the thought down and label it. Not with poetry. With tags.

- “Mood-generated.”

- “High certainty, low evidence.”

- “Old tape.”

- “Not actionable.”

It’s like putting a hazardous material sticker on a container. It doesn’t make the container disappear, but it does prevent me from sipping it absentmindedly while pretending it’s tea.

The Bitter Joke

The most ridiculous part of the whole affair—the part that would be funny if it weren’t my daily furniture—is how quickly I grant authority to my ugliest mental state.

If I’m slightly hopeful, I interrogate it like a suspicious customs officer. What are you doing here? Show your documents. Prove you’re not delusion. If I’m miserable, I hand it a chair and offer it snacks. Welcome, sir. Please, take the microphone.

Why? Because misery aligns with my fears, and fears always feel like wisdom. Fear is ancient. Fear kept our ancestors alive long enough to reproduce. Fear has the atavistic prestige of survival. Hope feels like a luxury item, like imported cheese: probably fake, probably adulterated, probably too expensive for my constitution.

So I accept the cheap local brew—my own ruminative piss—because it is familiar, because it is bitter in the way I’ve been trained to believe truth must be bitter.

That’s the snare in one sentence: I equate pain with accuracy. And then I wonder why I live like a man who keeps licking a cracked battery to “check” if it still works.

A Small Defiance, Quietly Embarrassed

Tonight the room will do its usual thing again. The winter air will press itself against the walls. The fan will turn. The phone will offer me a buffet of things to be outraged by. My brain will attempt, with its familiar zeal, to build a cathedral out of my shortcomings and then kneel before it.

I will not win some heroic victory over it. That kind of story is for motivational speakers and people selling courses.

But I can do one small defiant act: I can refuse to confuse the drink with the truth. I can look at the thought—You are finished—and say, in my most tired, unromantic voice, You are a symptom, not a prophecy.

I can take the picture of the grinning man swallowing yellow certainty and see it for what it is: a cartoon of my own gullibility. And then I can do something almost insultingly ordinary, something that doesn’t flatter my misery with attention.

I can close the blister pack. I can put the glass in the sink. I can open a book and let someone else’s sentences borrow my nervous system for a while.

Or—because I am exactly the kind of person who does this—I can delete a paragraph I just wrote, not because it’s “bad,” but because I can feel the ruminative tone trying to turn itself into doctrine, and I don’t want to publish doctrine; I want to publish evidence of a mind wrestling with itself and occasionally refusing to drink what it produces.

The light goes off with a soft click. In the dark, my brain will still try to hand me that cup. In the dark, I can still decide—quietly, without drama, without holiness—not to raise it to my mouth.