Melancholia to Methane

The mattress is on the floor because I have, for years now, been running an experiment in “minimal viable dignity,” and the results are in: dignity is not a thing you can bootstrap from dust and lint and a phone with a cracked screen.

December in Kolkata arrives like an old clerk with a stamp—thunk, thunk, thunk—approving every pollutant, every bad decision, every damp wall, every lungful of brown air, every unacknowledged life. The city goes into its winter trance, the inversion cap settles like a greasy lid on a pot, and we all simmer gently in our own exhaust while pretending it’s “pleasant weather.” It is pleasant, yes, in the same way a sedative is pleasant—quieting, flattening, reducing you to one long resigned exhale.

I lie there and I can smell the civic contract. It smells like burnt plastic and frying oil and damp paper and that peculiar sourness of old concrete that has been losing to water for decades. Somewhere, someone is burning something they should not burn, because the municipal system has the moral backbone of a jellyfish, and the rest of us are the aquarium.

My phone is a little glowing rectangle of doom. My laptop is a slightly bigger glowing rectangle of doom with a keyboard that remembers better days. The fan makes a sound like it is filing a complaint in triplicate. Outside, the city runs on a mixture of faith and fraud and diesel.

And in that mood—this thick, low-pressure mood where even my thoughts feel oxygen-deprived—I begin to entertain one of those ideas that is half metaphor, half insult, and half a sincere engineering proposal (yes, that’s three halves; welcome to my brain): what if my despair, and the despair of people like me, could be harvested like biogas?

Not harvested in the genocidal, cartoon-villain sense—calm down, inner psychopath, go sit in the corner and chew on your own shame—but harvested in the strictly chemical sense, the way a village digester turns cow dung into a blue flame and a cup of tea.

Because methane doesn’t care about my résumé. Methane is gloriously meritocratic: give it carbon, give it hydrogen, exclude oxygen, add time and microbes and a bit of warmth, and it will show up like a punctual bureaucrat and do its job.

Melancholia to Methane

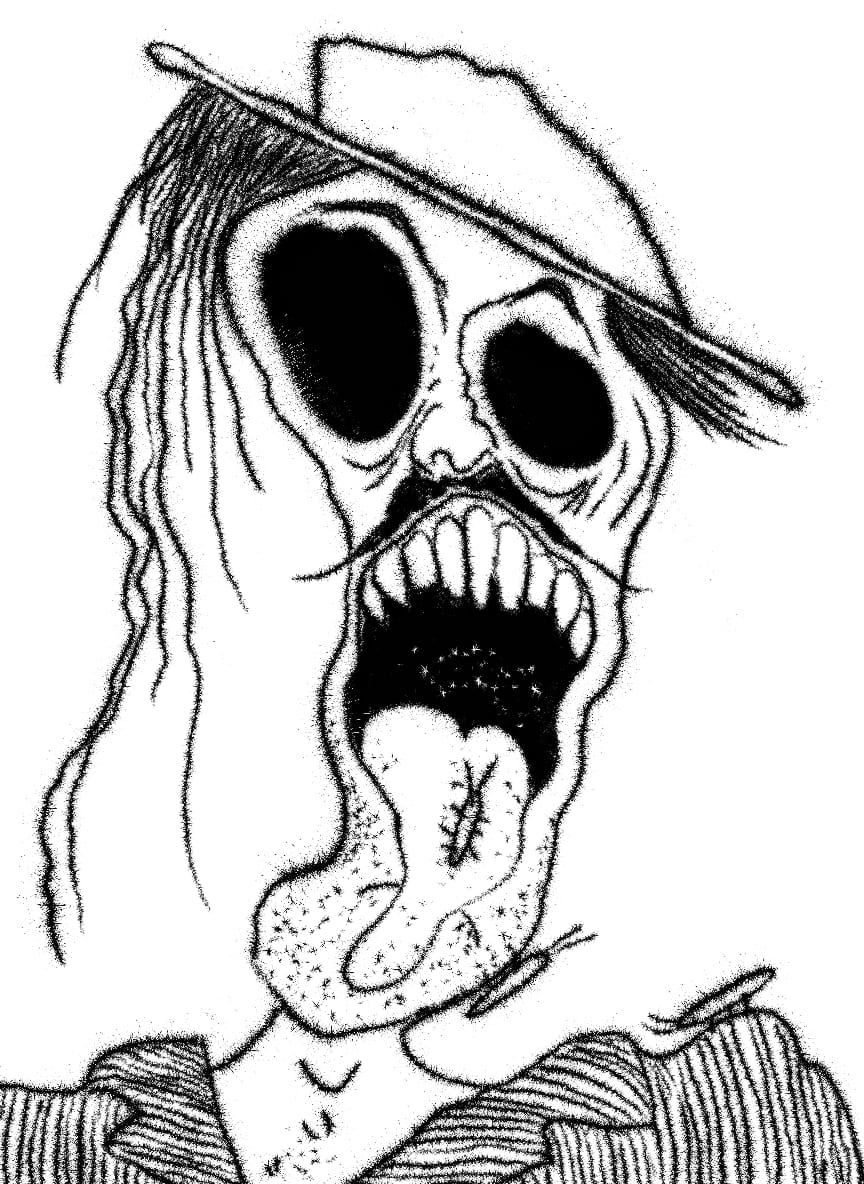

The romance of decomposition. The chemistry of giving up—transmuted into power, into motion, into light.

The Greeks, those dramatic geniuses, gave us “melancholia” from melas (black) and cholé (bile), because they loved turning misery into bodily fluids. Which is fair. If you’ve ever been depressed, you know it is not an idea; it’s a secretion. It is something your body does to you, like an unrequested tax.

Methane, meanwhile, is named in a way that sounds like a Victorian aunt—methane, methanol, methyl—all that tidy nineteenth-century nomenclature, as if chemistry were a polite parlor game and not, in reality, a catalog of ways matter can betray your expectations. Methane is CH₄, a carbon with four little hydrogens clinging to it like anxious children, and it burns beautifully: blue flame, clean-ish story (until you remember leakage, climate forcing, and the minor detail that we are cooking the planet like a forgotten potato).

But that blue flame is hypnotic. It is the dream of relevance. Look, it says, even your waste can do work.

And so my mind—always eager to be useful, always eager to be cruel—starts drafting a fantasy apparatus.

In the fantasy, there is a plant, maybe somewhere near the edge of the city where the land is cheap and the conscience is cheaper. A shed, tin roof, puddles, a few bored dogs with the streetwise posture of old philosophers. Inside: digesters. Big cylindrical tanks, painted an optimistic green that no one believes in. Pipes snaking like intestinal thoughts. Gauges. Valves. The gentle, constant burbling of anaerobic life doing what it does best: taking yesterday’s organic tragedy and making tomorrow’s combustible gas.

And then—this is the part where my brain gets lyrical and disgusting in the same breath—there is a feedstock pipeline called The Overeducated Underemployed Middle-Aged Man.

We are plentiful. We are moist with regret. We are rich in carbon. We are, in the blunt thermodynamic sense, energy-dense sadness.

You could shovel in our failed plans, our unfinished projects, our GitHub repos with three commits and a grand title, our half-learned theorems and abandoned notebooks, our careful moral scruples that have never once paid the rent, our long emails to powerful people that begin “Dear Sir” and end in silence.

You could shovel in our WhatsApp forwards from relatives, the ones that are half propaganda and half spiritual blackmail, and you could watch them dissolve into slurry.

You could add my particular vintage of gloom—North Kolkata, English-medium education, a childhood of books like a staircase to nowhere, a mind trained to be precise in a world that rewards the vague and the loud—and the digesters would purr.

Then the gas rises. The methane is captured. It is scrubbed—hydrogen sulfide removed, moisture condensed—because even in fantasies I believe in maintenance.

And then the methane goes to a generator. The generator makes electricity. The electricity goes to a data center. The data center runs the glowing pantheon of LLMs, those enormous stochastic parrots with their velvet tongues, composing speeches for ministers and captions for weddings and apologies for corporations, all of it lubricated by the invisible combustion of someone’s disappointment.

This is what my mind does when it is both depressed and literate: it turns grief into a diagram.

The Oxygen Leak

The thing about biogas—about any digester—is that it only works if you stop letting oxygen in. Oxygen is the busybody aunt who ruins the whole party. Methanogens, those archaea with their ancient, quiet competence, do not want oxygen. They want darkness and patience and a steady diet. They want the world to stop fussing and let them metabolize.

There’s a lesson there, of course, and I hate lessons, because they smell like TED Talks and smugness. But the lesson stalks me anyway: my own mind is an oxygen leak.

I cannot just rot. I have to narrate my rotting. I have to annotate it, footnote it, compare it to American culture, relate it to colonial history, drag in an etymology, perform an autopsy while the patient is still insultingly alive.

The city outside provides endless material for this. Kolkata is a palimpsest—a manuscript scraped and overwritten so many times that the older text still bleeds through, ghost-writing the present. A British street plan slapped on older lanes; colonial institutions with postcolonial slogans; marble plaques and broken sidewalks; grand buildings with wiring that looks like nervous tissue exposed.

And everywhere: stories. Each one a tiny anaerobic pocket of decay, producing its own little bubble of gas.

The political class—state and center, whichever jersey they wear this season—feeds on narrative the way methanogens feed on acetate. They take complex reality, chew it into slogans, and burp out certainty. Certainty is the most profitable gas in India. Certainty can run engines far bigger than methane.

In Bengal we have our own local theater—our own court jesters and court executioners—our own vocabulary of “development” that somehow never develops the one thing you can’t fake: competence.

And the center, with its grand national mythmaking, its chest-thumping pageantry, its high-definition pieties, plays the same game at larger scale. Different costumes, same stage directions: distract, divide, deify, repeat.

Sometimes I think the real product of politics is not policy but fatigue. A population too exhausted to verify anything, too stressed to think slowly, too distracted to notice that the ground beneath them is being quietly sold.

And in that fatigue, the LLMs bloom like algae. They are perfect for a world that wants language without accountability. They will generate a thousand paragraphs of plausible nonsense with the cheerful obedience of a well-trained court scribe. They will say what you want, not what is true, unless you build them—painfully, deliberately, annoyingly—around truth.

That’s the rub, isn’t it. I was trained in computer science, in the old-fashioned sense: logic, constraints, structure, the intoxicating hope that if you define things clearly enough you can make the machine behave.

Then the world pivoted to systems that behave like crowds: statistical, emergent, suggestible, brilliant and unreliable the way a committee is brilliant and unreliable.

And now, the louder people say “AI will change everything,” the more it feels like watching a drunk man promise to build a cathedral because he found a hammer.

None of this is the machine’s fault. The machine does what it does. My bitterness is aimed at the human layer—the managerial, ideological layer—that wants the appearance of intelligence without the inconvenience of thinking.

The methane fantasy returns because it is, in a perverse way, honest. It admits that something has to be burned. It admits that energy comes from somewhere. It admits that inputs matter.

A data center is not a cloud; it is a furnace with better marketing.

The Export of Pathologies

In America—when I lived there, back in the years when I still believed geography could rescue a person—I saw the same basic truth wrapped in better infrastructure. The roads worked. The systems pretended to be neutral. The professionalism was a kind of social lubricant. You could be an odd little foreigner and still get a lease, a job, a coffee, a life.

But even then, beneath the polished surfaces, there was a hunger. America runs on appetite. It consumes people the way an engine consumes fuel. Some people come out as executives. Some come out as ash.

And now—post-2016, post-everything, in this long era of Trumpism whether Trump is in the room or merely haunting it like a persistent odor—the appetite has become a personality. The culture has learned to treat cruelty as entertainment and ignorance as identity.

It is not unique to America, of course. We are all learning this curriculum. We are all being trained, by algorithms and incentives, to prefer outrage to understanding.

But America exports its pathologies with the efficiency of a global brand. If America sneezes, the rest of us catch pneumonia and then argue about whether pneumonia is “anti-national.”

So there I am, in Kolkata, inhaling my city’s winter breath, watching the world’s richest country flirt with authoritarian aesthetics while my own country perfects the art of calling any question a betrayal.

And I think: what is a man like me for?

This is the question I keep circling like a vulture that can’t find a decent carcass.

I am not poor enough to be politically interesting. I am not rich enough to be politically protected. I am not connected enough to be useful. I am not obedient enough to be employable. My virtues—precision, skepticism, candor—are like owning a high-quality umbrella in a town that has outlawed rain.

The economy has become a carnival of performative competence. Job posts read like fiction. “Rockstar.” “Ninja.” “10x.” “Hustle.” These words are not requirements; they are incantations. They are meant to summon a young person who has not yet realized that “passion” is often code for “unpaid overtime.”

And the apocalyptic twist is that even the nitwits—my beloved nincompoops, my cherished ninnies—are not safe. The carnival will eat them too. Automation doesn’t discriminate between sincere mediocrity and pretentious mediocrity. It will take your tasks, then your title, then your identity, then it will sell you a subscription to the simulation of your own usefulness.

In that future, my methane plant becomes almost tender. At least it offers a role. At least it says: you are not useless; you are biomass.

The Blue Flame

I know how grim that is. I know. But depression is the art of accepting grimness as realism. Hypomania, my other uninvited roommate, then swings in and says: Yes, but make it funny. Make it baroque. Make it science.

So I start riffing. I start imagining the brochure.

“Welcome to the Melancholia-to-Methane Initiative. We accept: failed entrepreneurs, disappointed idealists, honest engineers, burnt-out teachers, unrecognized writers, and middle-aged men who keep saying ‘I could have’ as if ‘could have’ were a currency.”

“Drop off your self-pity between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. Please remove all oxygen. No gods allowed in the digester.”

The digester doesn’t care about ideology. It cares about chemistry.

This is, perhaps, why the idea comforts me: it proposes a universe where rules exist and are enforced. The microbes do not take bribes. The enzymes do not forward WhatsApp rumors. The archaea do not hold press conferences.

They just work.

Sometimes I wish I could be that simple.

But I can’t. I am a human primate with a nervous system that evolved to fear exile, crave status, and invent stories. I live in a city that is itself a story—“City of Joy,” that famous marketing hallucination—and I cannot entirely abandon the longing to be seen as something other than waste.

And this is where my own complicity creeps in, like damp through a wall.

Because I am not merely a victim of the system. I am also, frankly, lazy. Not in the cartoon sense—my mind works like a factory that never shuts down—but in the bodily, executive-function sense. I postpone. I avoid. I let drafts rot. I treat my own life as a document to be revised later, as if later were guaranteed.

I am vain. I want to be right. I want my bitterness to be elegant. I want my insults to sparkle. I want the world to recognize my pain as well-written pain, which is a ridiculous desire, and yet there it is, squatting in my psyche like an unpaid tenant.

I am fearful. I fear ordinary failure more than grand failure, which is why grand failure attracts me: it comes with a narrative. Ordinary failure is just you, quietly, not doing the thing.

I tell myself stories about structural injustice—and God knows there is plenty of that, enough to stockpile for decades—but I also use those stories as a blanket. Sometimes the blanket warms. Sometimes it smothers.

So, yes, the methane plant is a fantasy of usefulness. But it is also a fantasy of abdication: a way to imagine that my decline is productive rather than merely sad.

And then the city intervenes, as it always does, with something embarrassingly concrete.

A scooter backfires. A dog barks. The neighbor’s TV emits a sermon disguised as entertainment. A mosquito finds the one square centimeter of skin I failed to cover. The practical world insists on its details.

I sit up, irritated, and I think about how methane is actually captured in landfills—pipes driven into mountains of garbage, vacuum systems drawing out gas. It’s not romantic. It’s not philosophical. It’s a maintenance problem. It’s engineering. It’s budgets, corrosion, leak detection, safety protocols, the constant risk of explosion.

In other words: reality.

And I realize, with the faint sting of clarity that depression occasionally grants, that my real complaint is not that I’m compost. We are all compost. Homo sapiens is a brief biochemical stunt. The universe is not sentimental about our plans.

My complaint is that the system is wasteful.

It wastes human potential the way Kolkata wastes water: everywhere, all the time, with a shrug. It wastes intelligence, sincerity, patience, craft. It rewards loudness. It rewards loyalty to the tribe. It rewards the ability to emit confidence without evidence.

It turns honest people into anxious people, then sells them “mindfulness” as if breathing were a product.

And the reason it can do this is that we have never properly taught people how to think. Not in the slow, methodical, pleasure-of-clarity way. We teach them to pass. We teach them to memorize. We teach them to worship marks. We do not teach them epistemology—the art of knowing what you know and knowing what you don’t. We do not teach them how to be uncertain with dignity.

So they become easy prey: for gurus, for politicians, for scams, for ideologies, for algorithms, for any machine that can mimic certainty.

This is where my own training becomes a kind of curse. I see the cracks. I cannot unsee them.

I watch people treat an LLM’s output as authority, and my brain screams: “It is a probability machine in a costume!”

I watch people treat propaganda as patriotism, and my brain screams: “You are confusing obedience with love!”

I watch the job market turn into a roulette wheel, and my brain screams: “This is not meritocracy; this is musical chairs with better fonts!”

But screaming in your head is not an intervention. It is just another gas.

So what do I do with my gas?

In the fantasy, I burn it. I turn it into electricity. I power the very system that makes me feel obsolete. It’s a perfect tragic loop, a Möbius strip of indignity.

In real life, I do smaller things.

I write. I delete. I rewrite obsessively. I fact-check myself and then forget what I checked. I read a chapter of something serious and then doom-scroll something stupid. I oscillate between wanting to build something and wanting to vanish into the wallpaper.

Some days I can’t stand Kolkata. The filth feels personal, like an insult delivered with bureaucratic consistency. The incompetence feels like a conspiracy, even when it’s just entropy wearing a uniform.

Other days, the city softens. A tea stall glows in the fog like a small, defiant lighthouse. A stray cat sits with the calm arrogance of a minor deity. A man on a bicycle carries vegetables as if performing an ancient ritual of persistence. Someone says “দাদা” in that casual Kolkata way that makes you feel, briefly, like you belong to a species.

Belonging is a narcotic. It doesn’t solve anything, but it changes the flavor of despair.

And I realize—again, not as a moral, not as a poster slogan, but as a quiet mechanical truth—that my relationship with this city is itself anaerobic. I keep returning to it because it is sealed. It excludes oxygen. It keeps my past from oxidizing into something else.

If I left, I might become someone different. Different is risky. Different requires effort. Different might fail in new ways.

So I stay, and I rot, and I write about rotting as if writing were a form of composting.

Maybe it is.

Compost is, at base, a choreography of organisms breaking down what once seemed solid. It is life feeding on death feeding on life. It is not noble. It is not tragic. It is the normal metabolism of the planet.

I am not special. My sadness is not special. My anger is not special. My vulgar metaphors are not special, though I do try to make them entertaining because what else is a man to do with his own interior sewage?

But I am, inconveniently, alive. Which means I still have choices, even small ones, even feeble ones that do not look heroic on LinkedIn.

Tonight, for instance, I can choose not to let my self-loathing metastasize into fantasies of harming “people like me,” as if I were some petty god of eugenics. That road leads nowhere but moral rot.

I can choose to keep the satire pointed upward—at power, at hypocrisy, at the cheerful cruelty of systems—and keep the tenderness pointed inward, even when I don’t feel I deserve it.

I can choose to make my methane into a small flame rather than a bomb.

The fan keeps complaining. The brown air keeps pressing against the windows like a dirty palm. Somewhere, a loud man is telling other loud men what to believe.

I reach for my laptop. I open a draft. I stare at the blinking cursor—the tiniest, dumbest heartbeat—and for a moment it looks like a little pilot light.

Not hope, exactly. Not salvation. Nothing cinematic.

Just a small, stubborn blue flame, fed by whatever I’ve got left, in a city that loves to call itself joy and rarely bothers to earn the title.