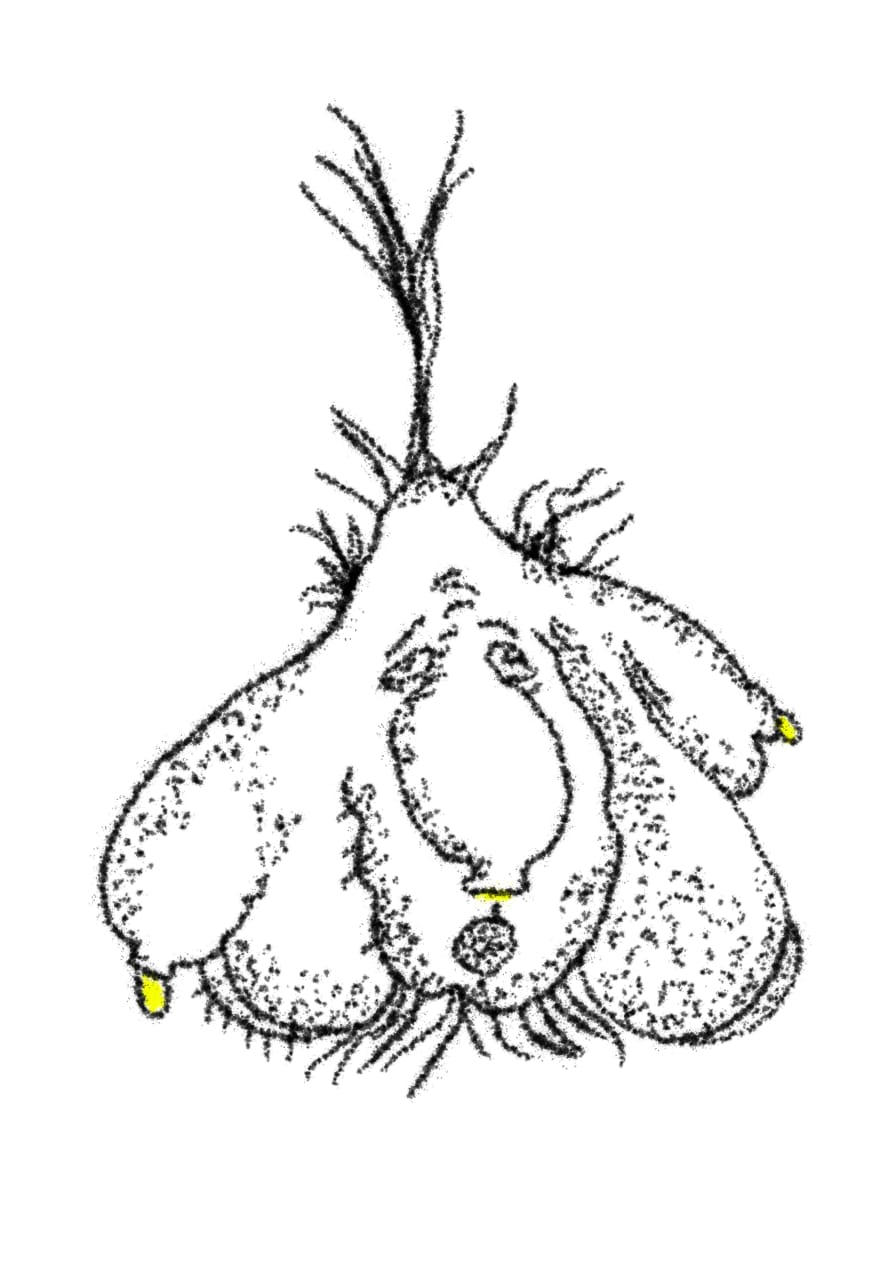

Garlic

The lugubrious garlic is sitting on my table like a small, pale tribunal, six little cloves in a loose pile, papery skins curled like old correspondence, the whole thing smelling faintly of honest work and culinary violence, and I am sitting beside it in that Calcutta December damp that gets into your bones the way bureaucracies get into your life—slowly, thoroughly, with a talent for making everything feel slightly heavier than it ought to.

December 13. Not a holiday, not a birthday, not a date with any cosmic myth attached to it, just a day with a particular texture in my head: low ceiling, low mood, low battery, the sort of day where the mind becomes a miser and rations hope like kerosene.

So naturally I do what any modern ape does when it feels small and powerless: I poke a glowing rectangle and ask it a stupid question.

How many r in garlic.

And the newest, shiniest, trillion-dollar-algebra-of-language contraption—running in its grand “extended” thinking mode, humming away on some faraway rack of GPUs, surrounded by fanboys in ceremonial foam—manages to answer wrong with the calm assurance of a man who has never been wrong in his life because he never checks.

The irony is so clean it’s almost literary. I am, on this low day, standing in front of a machine that can summarize a book I haven’t read, translate a poem I don’t understand, impersonate a professor I once feared, and it stumbles on six letters like it slipped on a banana peel placed by a bored kindergarten teacher.

But now, because I have been scolded by reality, I do the one thing that the machine—apparently—did not do in the moment: I look at the object itself.

G-A-R-L-I-C.

There is one r. Exactly one. The third letter. Right there, shameless, ordinary, not hiding behind anything, not an “edge case,” not a “sampling artifact,” not a philosophical debate about what it means to have an r. It is simply there, the way a debt is simply there, the way grief is simply there, the way the damp on your wall is simply there.

And I feel that familiar little hot ember of irritation that isn’t quite anger and isn’t quite sadness, but the hybrid creature that lives between them: the feeling that the world is increasingly run by confident people who do not verify.

That’s the thing I can’t stop circling. Not the mistake itself—anyone can miscount while distracted—but the style of the mistake, the self-possessed certainty with which it was delivered. It’s the rhetorical equivalent of a man handing you a cup of tea with a dead fly floating in it and then looking offended when you mention the fly, as if your standards are the real problem.

Confidence, in 2025, has become the most heavily subsidized hallucination.

And this is why my mind—being the cranky, bookish, self-torturing machine that it is—slides sideways into negative numbers, because negative numbers are the oldest story we have about things that exist but offend polite society.

The Minus Sign and the Social Life of Reality

Negative numbers are not hard in the way calculus is hard. They’re hard in the way admitting you’re in debt is hard. They make perfect sense operationally—subtracting, owing, reversing direction—but emotionally they feel like an insult.

You can practically hear the human animal’s ancient complaint: how can there be less than nothing? How can the cupboard be emptier than empty? How can the day be worse than bad?

The number line is a respectable street. To the right you have the tidy houses——where arithmetic behaves like a well-trained civil servant. To the left is the neighborhood with the scandalous reputation, where debts and temperatures and losses and failures live, and where people go only when they have to, like visiting a relative who tells the truth too loudly.

So for centuries, the intellectual world did that very human thing: it used negatives when it needed them but treated them like a moral failing.

Enter Michael Stifel, a sixteenth-century German monk and mathematician, a man perched right on the seam of medieval piety and modern computation, wearing the religious costume of his time while quietly rearranging the machinery of numbers behind the curtain.

Stifel called negative numbers “absurd,” “fictitious,” numeri absurdi—as if to say, yes, yes, I know these are indecent, I’m only letting them in because they’re useful, like hiring a brilliant accountant who unfortunately drinks at breakfast.

It’s a fascinating compromise: the mathematics begins to admit what reality has always been doing, but the culture insists on scolding it for being impolite.

Because Stifel wasn’t an idiot. He understood that the rules get cleaner when you let the full set of numbers exist. He worked with negatives in algebraic manipulations; he helped push arithmetic toward something more systematic. But he still felt compelled to label the left side of the line as a kind of conceptual slum.

This is not a moral failing of Stifel; it’s a documentary record of human squeamishness.

And it is so familiar.

The modern world has no problem with negative numbers. We have a problem with negative feedback. We have a problem with a minus sign applied to our myths: minus points on a benchmark, minus trust in a product, minus optimism in a press cycle. “People do not approve,” as an older mathematician might have said, and so the entire culture tries to alchemize minus into plus by changing the font.

Stifel’s Other Tricks: Powers, Exponents, and the Temptation of Neatness

Stifel did something else that feels almost charming now: he played with powers of two and exponent tables in a way that hinted at the future.

To a modern brain, exponents are like furniture. They’re just there. You grow up around them. But in Stifel’s time, the symbolic machinery of algebra was still being assembled, bolt by bolt, and he was one of the people doing the tightening.

When you write a table of powers——you are building a ladder. And the moment you realize the ladder can also go down——you have, without fanfare, invented the idea that exponents can be negative. The ladder has a basement. The basement is useful. The basement is also where polite society insists nothing should be stored.

Multiplication turning into addition through exponents is the sly magic behind logarithms, and while Stifel didn’t bottle it the way Napier later did, you can smell the proto-logarithmic perfume in the room: the sense that there’s a structural trick here, a way to make gnarly operations behave like simpler ones by changing the coordinate system of thought.

Mathematics, at its best, is a machine for turning hard problems into easier shapes. It’s a way of rotating the mental object until it fits through the door.

Which makes it all the more tragic—and funny, in a bleak way—that Stifel, this man of structural insight, also fell into the oldest trap in the human cabinet: confusing pattern-making with truth.

The Calculated Apocalypse

Stifel predicted the end of the world. Not poetically, not metaphorically, but numerically, on a schedule. He treated sacred text as a coded dataset, ran it through his interpretive engine, and emerged with a date and time, the way a modern pundit emerges from a spreadsheet and declares the economy “definitely” heading for a soft landing because the line wiggled reassuringly last quarter.

It did not end.

The world has an almost rude habit of continuing.

I imagine the scene because it’s too perfect: the faithful waiting, the clock ticking, the air thick with anticipation, and then—nothing. A rooster crows. Someone’s stomach growls. A child complains. The same petty ordinary life persists, indifferent to the grandeur of the calculation.

And that, to me, is the true moral of Stifel, more than the “absurd numbers” label. The moral is that a person can be genuinely brilliant at formal manipulation and still be gullible about what the manipulation implies.

The human mind loves the sensation of inevitability. It loves a conclusion that feels ordained. It loves the aesthetic of certainty.

And this is why a modern model can be wrong about garlic while sounding serenely right, and people will still declare a win. They are not worshipping accuracy. They are worshipping the performance of competence.

The Baron Who Hated Fog

Baron Francis Maseres—an 18th-century English mathematician with the soul of a courtroom clerk and the temperament of a man who wants his universe well-lit and properly indexed—shows up a couple centuries after Stifel still clutching his pearls about the minus sign. He argued (in his 1758 Dissertation on the Use of the Negative Sign in Algebra) that the whole business of “isolated” negative quantities is basically “nonsense” and “unintelligible jargon,” not mathematics but a kind of symbolic hooliganism that “darken[s] the very whole doctrines of the equations” and makes simple things obscure, as if the left side of the number line were a fog machine smuggled into the lecture hall.

I find this perversely comforting, because it proves that even in the age of powdered wigs and Enlightenment self-congratulation, people were still doing the same old human thing—accepting the bookkeeping reality of debt and loss in practice, while refusing to grant it metaphysical citizenship on paper.

Bhāskara and the Line “People Do Not Approve”

Now let me drag in Bhāskara II, because if Stifel is the European monk negotiating with the squeamishness of his age, Bhāskara is a different sort of negotiator—Indian, twelfth century, mathematician and astronomer, writing in a tradition that had long been comfortable treating negatives as debts and positives as fortunes.

The Indian mathematical tradition used that debt/fortune framing very naturally. If you’ve ever had to keep track of who owes whom in a real market, you don’t need a metaphysical argument for negative numbers; you need a ledger that doesn’t lie.

Bhāskara could compute with negatives. He could use them in algebraic rules. But when certain problems produced negative answers—especially in contexts where the answer was supposed to correspond to a “real” physical quantity—he made a remark that, to me, is one of the most human lines in the history of mathematics: people do not approve.

That sentence is doing a lot of work. It’s admitting that mathematics is not only about internal consistency; it’s also about what the culture is willing to swallow. It’s admitting that even when the logic is clean, the audience may still refuse the result because it offends their intuition, their metaphysics, their sense of propriety.

Bhāskara is not rejecting the minus sign because he cannot handle it. He is noting a social constraint. He is acknowledging that there’s a difference between what the symbol system permits and what the community finds acceptable.

And suddenly I feel less alone, because this is exactly what it feels like to live in a world that prefers comforting narratives over unpleasant arithmetic.

The world is full of things that are true and not approved.

A negative bank balance. A negative medical test. A negative review of a beloved institution. A negative thought in your head that you can’t evict by sheer optimism.

A language model that miscounts a letter while the crowd cheers.

Garlic as a Tiny Benchmark of Reality

So here is the corrected fact, nailed to the wall like a modest insect specimen: garlic has one r.

And I keep coming back to how small that is. Six letters. One r. A task so trivial that it feels almost insulting to talk about it seriously—like arguing with a grown man about whether the sun rises in the east.

But that’s precisely why it matters.

Because if you can’t reliably handle the small, checkable facts, then your elegance is ornamental. Your sophistication becomes theatre. Your metaphors become a kind of perfume sprayed over an unwashed body, and no amount of branding will turn that into cleanliness.

This is what quality control is, in its simplest, least glamorous form: you count the letters in garlic. You do not accept vibes as a substitute for verification. You do not permit the performance of competence to masquerade as competence itself.

And yes, the defenders will rush in with the familiar, technically correct litany: language models are probabilistic; tokenization; sampling; the system isn’t built for exact symbolic tasks; you should use tools; you should constrain; you should prompt; you should do this; you should do that.

Fine. I can recite the catechism too.

But the user—the ordinary, tired person with a small question—does not live inside your technical caveats. The user lives in the world where a confident answer implies reliability. Where tone is taken as a signal of truth.

So if the product is going to speak with confidence, it must earn that confidence. And if it cannot, it should learn to speak with humility.

The most dangerous thing in the world is a system that is wrong and smooth.

The Smelly Bengali Cynic as a Control Mechanism

This is the part where my own self-description, which is not kind, becomes a strange professional qualification.

OpenAI—or any of these modern firms that have become a hybrid of laboratory and religion—should hire a smelly brown deformed Bengali cynic for quality control.

Not because I’m special. Not because I’m a genius. But because I am temperamentally unable to participate in ceremonial applause. I do not have the gene for “Yes, boss, the demo was inspiring.” I have the gene for “Count the letters.”

And I will not, on principle, lick any metaphorical derrière for access. I will not pretend a product is ready because it has a nice name and a nicer launch video. I will not “fake stamp” a thing until it passes muster, because I have spent too long living in a country where fake stamping is a national sport and everyone acts surprised when the bridge collapses.

A cynic is not an optimist’s enemy. A cynic is a pessimist’s seatbelt.

A proper QC cynic would sit in the corner, uninvited, like a minus sign at a positivity conference, and keep asking the vulgar questions: does it work, does it hold, does it fail gracefully, does it admit uncertainty, does it tell the truth even when the truth is not approved.

Because this is what the public deserves, and what the fanboys will never demand. Fanboys want to feel part of the future. QC wants to keep the future from electrocuting the present.

Depression as a Negative Number

And now I come back to myself, because the essay was always going to come back to me, the way a dog comes back to its own mess.

Depression is a minus sign laid across the day.

It subtracts flavor. It subtracts ambition. It subtracts the sense that anything matters. It makes the simplest task—showering, replying to someone, eating—feel like lifting a refrigerator with your eyelashes.

When I’m in that state, my mind does to my own life what early mathematicians did to negatives: it calls it absurd, fictitious, not to be trusted. It says: your hopes are not real quantities. Your plans are imaginary roots. People do not approve.

And yet, some stubborn part of me keeps calculating anyway.

I keep reading. I keep writing. I keep peeling garlic. I keep doing arithmetic on my own moods, trying to detect patterns, trying to build a private ledger: today minus yesterday equals something; this hour minus that hour equals an improvement; this thought minus that thought equals a moment of quiet.

It’s not heroic. It’s just mechanical persistence. The smallest kind of dignity: the refusal to lie to myself about the numbers.

Stifel called negatives absurd and still used them, because the rules demanded completeness.

Bhāskara noted that people disapproved and still did the computations, because reality didn’t care about approval.

And here I am, in my own damp room, correcting a letter count because the smallest truth still matters more than the grandest performance.

The End That Doesn’t End

I crush a clove under the flat of a knife. The smell blooms instantly—sharp, rude, unmistakably real—like a fact that refuses to be softened by marketing.

One r.

That’s what garlic contains.

One small letter, one small correction, one small reminder that the world is made of checkable things if you’re willing to look, and that looking—actual looking, not applauding, not repeating slogans—is the closest thing I know to sanity.

I put the phone face down, not as a gesture of virtue but as a minor act of self-preservation, and I watch the papery skins curl a little more in the damp air, like tiny white flags.

Not surrender.

Just the quiet admission that even a minus day can still contain one honest count, one clean correction, one clove crushed into usefulness, and that’s about as much approval as reality ever asked for.